Hopkins’ poem ends with one thing greater than beauty and that is grace. Grace is what is revealed and operative in F O’C’s A Temple of the Holy Ghost. In a story full of some very unattractive characters the reader is led to see the affirmation of the title image: we are [ought to be] temples of the Holy Spirit; we should be like the tattooed Parker at the end of his story, the body of Christ.

O’Connor stories work in certain patterns. We are first introduced to fairly seriously flawed characters. Ruby Turpin, for example, who is proud and terribly self-satisfied, and O. E. Parker who is smug and lazy and extremely dissatisfied. In this story the main character, whose point of view carries the story, is a 12 year old “child,” proud, unattractive, and frequently unpleasant and mocking of those around her, yet she is also intelligent and perceptive.

Second, there is almost always a tension in the story between the main character and one or more of those around her or him. With Ruby the tension exists between her and most of those in the doctor’s office with her; the tension reaches its startling climax when Mary Grace throws the book and hits her in the head. With Parker the tension exists primarily between himself and his wife, Sarah Ruth, though it also occurs between himself and the 70 year old lady for whom he works. In A Temple of the Holy Ghost the tension exists between the never-named child and most of those around her, but especially with the two 14 year old convent girls who come to stay over the weekend with her and her mother. That they are two years older than the child is important because they have reached puberty and understand things that the child doesn’t.

The third aspect or characteristic of each short story involves the way the flawed character behaves that makes him or her subject to the responses of the surrounding characters. Ruby’s self-satisfaction overwhelms the doctor’s office until Mary Grace is insanely driven to respond violently; oddly, Mary Grace’s response is as humorous as it is shocking and understandable. Parker’s dissatisfaction leads to his lack of attention, which results in the tractor accident, which drives him (pun intended) the fifty miles to the city and the tattoo artist’s office. In the child’s case her pride and curiosity cause her to trick the two visitors into revealing what they saw in the tent at the fair, the encounter with the pious hermaphrodite.

The fourth element in the story is the way in which the usually violent response to the character flaw leads to the possibility of insight, as in the case of Ruby and Parker. Each will have to live out the rest of his or her life with the new understanding of self and reality. The operation of divine Grace in an O’Connor story operates entirely within the natural world through secondary causes. You might say truthfully, I think, that God uses our flaws and our contexts to bring us to vision and salvation. Sometimes, however, the character’s insight or vision occurs at a moment of death. Such is the case with the grandmother in A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Mrs. May in Greenleaf. In A Temple… the pattern works somewhat differently. The transforming encounter occurs as the two convent girls describe the “freak” who has revealed [pun intended] him/her self to his fairground audience; the so-called freak is a hermaphrodite, having both male and female genitalia. The revelation of this to the child leads to her third fantasy vision in the story: this time she imagines a kind of Pentecostal religious service which will be a counterpart to the Catholic Mass that occurs almost immediately after.

The fifth aspect of the story is the way in which the author’s imagination weaves a pattern in each detail throughout the story that reveals the real Idea of the story. I would say that the real meaning in the child’s story is the way in which matter, especially flesh and blood matter, reveals spirit. As with Mrs. Turpin’s story and Parker’s story the Ideas are there from the beginning. As we see in the opening paragraph, the unattractiveness of the central characters is emphasized and focused along with the controlling image of flesh and blood as the Temple of the Holy Ghost:

“ALL weekend the two girls were calling each other Temple One and Temple Two, shaking with laughter and getting so red and hot that they were positively ugly, particularly Joanne who had spots on her face anyway. They came in the brown convent uniforms they had to wear at Mount St. Scholastica but as soon as they opened their suitcases, they took off the uniforms and put on red skirts and loud blouses. They put on lipstick and their Sunday shoes and walked around in the high heels all over the house, always passing the long mirror in the hall slowly to get a look at their legs. None of their ways were lost on the child.”

The most important element in the opening is the attitude toward the central image: the convent girls see it only as a joke, an image or idea to laugh about, in a sense an image for fun and laughter for a person who is on the “inside,” or in on the secret knowledge, so to speak. Tied to the Temple image is the girls’ immediate unattractiveness, especially Joanne’s. Her appearance is positively ugly. What the story accomplishes is the transformation of this attitude of”silliness” regarding the Idea until by the end of the story the idea of flesh and blood revealing spirit is the central reality of life, the child’s life at least, as well as the life of the church, its central reality as primary Temple too (pun intended).

The third aspect of the paragraph is the mirror and its reflecting capacity. First, one might notice that the girls change out of their convent uniforms into their secular clothes as if the two realms, sacred and secular, were separate realities. The girls then use the mirror to admire their legs, their flesh and blood bodies, so to speak. Again, what flesh and blood reveal by the end of the story is the presence of spirit, the Holy Spirit, not only in flesh and blood but in the entire material world, as the two realms are brought together in the Mass, in the child’s imagination, as we shall see in a bit. Looking again at the opening paragraph we find that the convent from which the girls come is “Mount St. Scholastica,” the name pointing to the most important theologian, Scholastic theologian, in the Catholic Church—St. Thomas Aquinas. Here is one of those details that reoccur throughout the story and help reveal the story’s Idea. St. Thomas is the author of the Eucharistic hymn sung at Mass and he was called “the dumb ox,” an epithet the child applies to Wendell and Cory for their ignorance regarding the Latin hymn sung by the girls. As I have said every detail in the story contributes to the Idea of the story, its meaning.

The final detail in the quoted section reveals the presence of the child and her watchfulness. This presence is especially important as her mother prevails upon the girls to explain “the joke”:

“She asked them why they called each other Temple One and Temple Two and this sent them off into gales of giggles. Finally they managed to explain. Sister Perpetua, the oldest nun at the Sisters of Mercy in Mayville, had given them a lecture on what to do if a young man should—here they laughed so hard they were not able to go on without going back to the beginning—on what to do if a young man should—they put their heads in their laps—on what to do if—they finally managed to shout it out—if he should “behave in an ungentlemanly manner with them in the back of an automobile.” Sister Perpetua said they were to say, “Stop sir! I am a Temple of the Holy Ghost!” and that would put an end to it. The child sat up off the floor with a blank face. She didn’t see anything so funny in this.”

While the transformation begins in the first sentence of the story, here we begin to see how the perspective of the child will carry the real meaning of the story. She doesn’t “see anything so funny in this.” First is the child’s understanding that the Temple image is serious. We might even say that the end is here contained in the beginning, for shortly after this revelation, we find a new attitude toward the governing image:

“Her mother didn’t laugh at what they had said. “I think you girls are pretty silly,” she said. “After all, that’s what you are—Temples of the Holy Ghost.”

The two of them looked up at her, politely concealing their giggles, but with astonished faces as if they were beginning to realize that she was made of the same stuff as Sister Perpetua.

Miss Kirby preserved her set expression and the child thought, it’s all over her head anyhow. I am a Temple of the Holy Ghost, she said to herself, and was pleased with the phrase. It made her feel as if somebody had given her a present.”

First, the child’s mother takes the idea seriously and is thus identified with the girls’ teacher, Sister Perpetua. Historically, Perpetua was one of the first female martyrs for the Christian faith. Thus, you might say, we can see how truly serious the idea is in the beginning, both historically and thus in the story, even though the girls maintain their perspective, though they are “astonished” to find in the mother “the same stuff” as in Sister Perpetua. The story is the child’s and therefore her attitude becomes the most important. While the child arrogantly dismisses the understanding of Miss Kirby whom the child doesn’t really know, the child now understands the idea as a “gift,” a “present.” And that, of course, is what the image of being a temple is all about. The presence of the Holy Spirit within is a gift of Grace, freely given. As Parker’s direction was subtly changed by his vision of the tattooed man at the fair, the child’s “ direction”is subtly changed here. What, for example, does the gift mean.

While as I have said before each detail in the story reveals the story’s meaning, yet there are two major encounters before the end that stand out. The first is the exchange of songs by the Pentecostal boys and the Catholic girls. The second is the child’s fantasy vision after learning what is present in the tent (tabernacle) at the fair. Each element moves our understanding toward the ending. First, Wendell and Cory sing two hymns to the girls as if they were love songs, which of course they are; the girls in turn sing the untranslated Eucharistic hymn, the tantum ergo, which is also a love song, St. Thomas’s love song to Christ and the “real presence” in the bread and wine. A translation is worth reading:

Down in adoration falling,

Lo! the sacred Host we hail;

Lo! o'er ancient forms departing,

newer rites of grace prevail;

faith for all defects supplying,

where the feeble senses fail.

To the everlasting Father,

and the Son who reigns on high,

with the Holy Ghost proceeding

forth from Each eternally,

be salvation, honor, blessing,

might and endless majesty. Amen.

Our human senses are weak, keeping us from seeing what is truly present in the Eucharist during the Mass, the real body and blood of Christ. What enables the (Catholic) Christian to say “Amen” to this element is of course faith. Faith is what enables the person to affirm that reality. It is interesting that in the Coen brothers’ film Hail Caesar, George Clooney, the Roman centurion standing before the crucified Christ on his cross, makes a tremendous speech regarding the man whom he had met once before. The problem is that the actor forgets the transforming word, faith, thus leaving the world of the movie stuck in its pervasive secularism. As in Aquinas’ hymn, without faith the person is blind. Faith, however, the gift of the Holy Spirit, enables the person to see the presence of God, not only in the Eucharist in the story but in the whole material world. In other words the sacred and the secular will become one in the story.

Before we get to the end though we need to see the absolutely necessary element to complete the pattern, the Idea, and that is the presence of the freak. Like the ark of the covenant in ancient Israel, the freak is found in a tent in the fair, where their is again diversity, males on one side of the tent and females on the other; there is, however, a disturbing unity of sorts, for the freak is a hermaphrodite, having both male and female genitalia. The crucial element is in what he says to the divided audience about how his “condition” occurred. As the convent girls reveal to the child, the freak accepts his situation as being the consequence of God’s will. And like Jesus in the garden before his passion, he doesn’t “dispute” it. The central thing that happens in this scene after the girls explain what they saw in the tent is that the child has a fantasy vision wherein she imagines the freak (and herself) in the presence of a Pentecostal worship service:

[“Raise yourself up. A temple of the Holy Ghost. You! You are God’s temple, don’t you know? Don’t you know? God’s Spirit has a dwelling in you, don’t you know?” “Amen. Amen.” “If anybody desecrates the temple of God, God will bring him to ruin and if you laugh, He may strike you thisaway.

A temple of God is a holy thing. Amen. Amen.” “I am a temple of the Holy Ghost.” “Amen.”

The people began to slap their hands without making a loud noise and with a regular beat between the Amens, more and more softly, as if they knew there was a child near, half asleep.]

What the freak says takes us back to the first lines of the story. If you laugh and treat this condition as a joke, the freak says, God may strike you this way. We have come from the idea of one’s being a Temple as a joke to the perspective of absolute seriousness regarding the Idea. Here we are at the very heart of reality, especially as a vision in the child’s mind. The consequence of that vision becomes immediately apparent as, after accompanying the two girls back to the convent with her mother and in the grossly foul smelling Alonzo’s cab, the child finds herself (language deliberate] at the Mass being celebrated there:

[The child knelt down between her mother and the nun and they were well into the “Tantum Ergo” before her ugly thoughts stopped and she began to realize that she was in the presence of God. Hep me not to be so mean, she began mechanically. Hep me not to give her so much sass. Hep me not to talk like I do. Her mind began to get quiet and then empty but when the priest raised the monstrance with the Host shining ivory-colored (like the sun) in the center of it, she was thinking of the tent at the fair that had the freak in it. The freak was saying, “I don’t dispute hit. This is the way He wanted me to be.”]

Before this moment the child has discovered that by looking through several strands of her hair pulled across her eyes that she can see the sun (son); otherwise she must squint. During the Mass that occurs after that discovery, the child then has a moment where the two realms, following her confession of sin, are seen as one, the sacred and the secular together, wherein the freak is seen as the Host; thus in the (Catholic) Christian perspective, the freak becomes the bearer of the presence of God. Here we might remember Flannery’s justly famous comment at the party in New York when she was asked about the real presence in the Eucharist: “well if it’s just a symbol to Hell with it.” This story also testifies to how we understand the revealing capacity of matter, for the child’s final vision in the story affirms the unity of sacred and secular, the revealing capacity of matter, even as the child now simply “notes” the flesh of Alonzo whereas before she had treated him as a joke because of his disgusting appearance and smell. Now however the final vision we have in the story is the Eucharistic sun (son) and the path to it beyond the world , beyond [Dante’s] dark wood, in a dimension all its own . Lest we miss the fullness of the connection of the divine presence in the fair and the world, Alonzo from the front seat of his cab explains that the fair (and thus the freak) has been shut down by the current religious element assisted by the police, just as in NT times pre crucifixion:

[“They shut it on down,” he said. “Some of the preachers from town gone out and inspected it and got the police to shut it on down.”]

Following that identity, we see that final vision from the child’s perspective, the final image of the sun(son) in the story and the way to it (him):

[Her mother let the conversation drop and the child’s round face was lost in thought. She turned it toward the window and looked out over a stretch of pasture land that rose and fell with a gathering greenness until it touched the dark woods. The sun was a huge red ball like an elevated Host drenched in blood and when it sank out of sight, it left a line in the sky like a red clay road hanging over the trees.

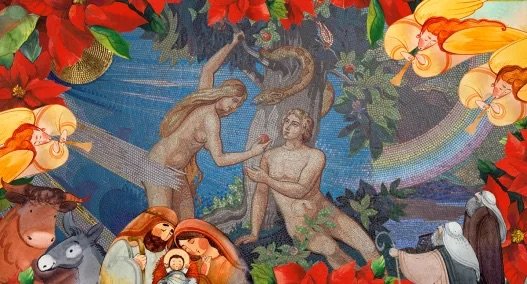

Image: 1/24/24 TCT Christ the Saviour with the Eucharist by Juan de Juanes (Vicente Juan Masip), 1545 – 1550 [Museo del Prado, Madrid.

[I haven’t proofed all the essay yet, thus who knows what the Imp of the Perverse might have changed or what some of my overly modified sentences might have ended up saying. As for now, it’s rewarding to me writing these things, for writing is discovery, such as the two realm image in the first paragraph. I saw it before but hadn’t thought about it. Writing is also somewhat exhausting! I hope these O’Connor essays are worth it out there too, so to speak.]